Archive of posts with tag 'airplane-crashes'

Mar 2014: Not Losing Planes: Lessons From MH370

In listening to a lot of people talk about the missing Malaysian Airlines MH370, I sometimes wonder if some of them truly have a sense of how remote some places in the world are, or how much it’d cost to monitor all that.

This article featuring a video with Mary Kirby talks about connectivity being the key. I don’t disagree.

However, a little over two months ago, I was on a ship sailing about 2,500 miles (4,000 km) almost due west from Valparaiso Chile to Easter Island. While it’s a remote place, it does have an international airport, cell service, most of that modern stuff.

What it doesn’t have? Satellite coverage in many bands for three of those five days of travel.

There’s something amazingly humbling (and somewhat terrifying) about being out of satellite range on what’s surely a cargo shipping route, especially when you’re sailing over water that is 13,000 feet (4,000 m) deep.

There are very few flights in the southern quarter of the world (by which I mean at least latitude 45° south). Here’s the entire list of settlements (where there’s at least 1000 people) south of 45°. That’s incredibly sparsely populated. Compare the latitudes with the northernmost settlements here.

So far as I know, there aren’t any southern polar air traffic routes the way there are so many northern polar routes. So probably the very last part of the earth that would get coverage is the kind of place where MH370 is believed to have been lost. I still think it’s too early to know that that’s the wreckage for certain, and I really feel for the people out there in the bad weather and rough seas doing that duty. Thank you.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t do something more in the future to make these search and rescue (where “rescue” is more about confirmation of what happened and the opportunity to not do it again) efforts less costly. For me, the turned-off transponder is the single weirdest thing: that, combined with the believed wreckage position, doesn’t make sense absent the information we now lack.

Mar 2014: NTSB Fatality Family + MH370 = Stress

On the ring finger of my left hand, I wear the wedding ring that once belonged to Pan Am Captain Arthur Moen. My late father-in-law, whom I never met.

Anyone who flies a lot fears the worst. Truly, on average, the risks in commercial aviation are low. Not zero, but low. Those of us who flew, say, 160,000 miles last year, some of that over the Indian Ocean, might be a wee bit more stressed about MH 370 than average folks.

This household, though, is a dual-NTSB-report family. A dual-NTSB-fatality-report family.

Rick and I were the same age when tragedy struck our families’ lives in very different ways.

My Side O’ The Family

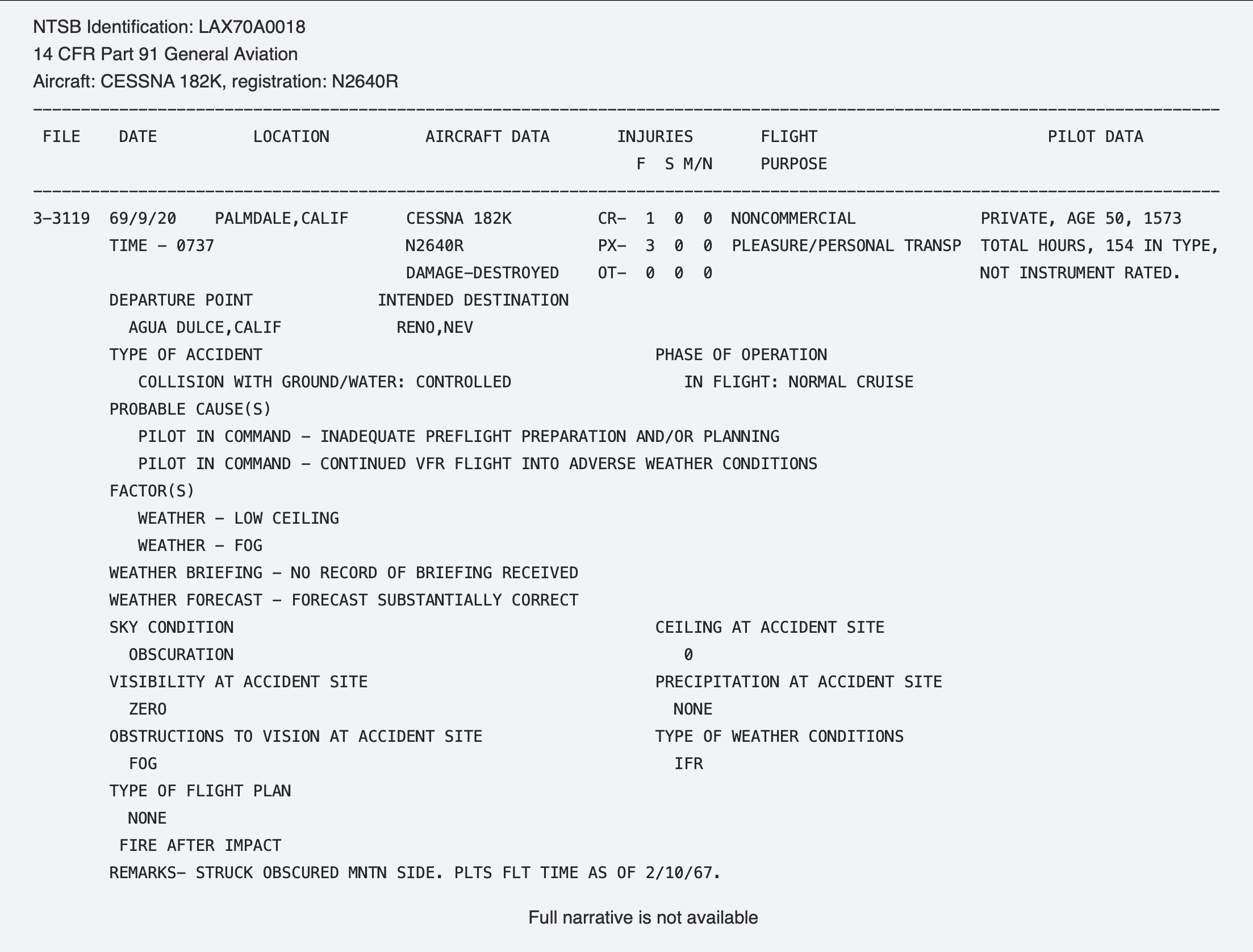

My stepfather had a Cessna 182, and it was on a leaseback, meaning other people could pay to fly it when we weren’t. One pilot with 1500 hours (quite a lot for a private pilot) decided to fly himself and three passengers to the Reno air show that year.

The pilot blew off the weather briefing that morning and, despite not being instrument rated (and the plane didn’t have the right gear for IFR), he took off in weather that required instruments. The fog was all the way to the ground at the place of impact.

The pilot mis-estimated where he was and, well, “struck obscured mntn side” says it all, doesn’t it?

Four people died. NTSB report follows.

Crash victim family members threatened to sue my family. There was an NTSB investigation, but our hands were clean. Still, when you’re a kid (or even an adult), it’s rather horrifying to think that the plane you flew in not so long ago flew full-speed into a mountain and caught fire.

Rick’s Side O’ The Family

Rick’s father’s case is the more famous one, a Pan Am cargo flight to Viet Nam.

The Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was an attempted takeoff with the flaps in a retracted position. This resulted from a combination of factors; (a) inadequate cockpit checklist and procedures; (b) a warning system inadequacy associated with cold weather operations; (c) ineffective control practices regarding manufacturer’s Service Bulletins; and (d) stresses imposed upon the crew by their attempts to meet an air traffic control deadline.

On Christmas Day, the flight left San Francisco, bound for Anchorage for refueling. The weather at the commercial airport was unsafe, so they landed at Elmendorf Air Force Base instead. The following morning (which, being Alaska in December, was completely dark), there were a number of irregularities in procedure during takeoff, and the time pressure wasn’t helping.

None of the three people survived the resulting crash.

The NTSB report resulted in a number of psychological studies on the relative effectiveness of checklists, though. Overall, checklist procedures at all airlines changed, albeit slowly.

The findings and related research were incorporated into other works. An example would be this dissertation. Or, perhaps strangely, the NTSB’s conclusions reached software development books like Model-Driven Development of Advanced User Interfaces.

Perhaps the most relevant book would be The Multitasking Myth (Ashgate Studies in Human Factors for Flight Operations):

However, accumulating scientific evidence now reveals that multitasking increases the probability of human error. This book presents a set of NASA studies that characterize concurrent demands in one work domain, routine airline cockpit operations, in order to illustrate that attempting to manage multiple operational task demands concurrently makes human performance in this, and in any domain, vulnerable to potentially serious errors and to accidents.

These were things that were largely unknown at the time. Pity we found some of them out the hard way.

If a job asks you to multitask? Better hope what you’re doing isn’t critical.

The Waiting

There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t wonder if the Asiana 214 report will be ready soon. I double-check to see I haven’t missed it.

Three weeks before the Asiana crash at my home airport, SFO, I was returning home from Alaska—my first trip there, and a place Rick understandably doesn’t wish to return to—when my United flight missed their approach and did a go-around. It was very strange looking out the window down at the airport from an angle you’re not supposed to see it.

While I hadn’t had a near miss, let’s just say that it rattled me. I didn’t tell Rick about the missed approach until the Asiana crash because it involved Alaska.

The only reason my wedding ring exists? Art had left it home to see if it could be adjusted by the local jeweler as it wasn’t fitting him right any more. Therefore it wasn’t in Alaska when the crash occurred.

So MH 370 —especially as someone who flew the airline last year (Maldives-Malaysia-Myanmar)—has me on tenterhooks.

We want to know what happened. We’re realists; we expect that there are no survivors. But we want to understand what happened. To feel reassured that’s not going to happen to us. We feel it more deeply than many other people because we’ve pored over other NTSB reports, become fascinated with tragic failures.

Family history has become part of our culture in gruesome ways. Rick keeps a photo of that particular Pan Am plane (the featured image for this post) at his desk at work. In my office at Apple, I kept a vintage ad for electronics marketing from Pan Am, also featuring that exact plane. Sadly, I don’t have the ad showing the tail number, but I have seen a copy. I just saw it minutes after it was sold. The ad I do have, though, was clearly taken in the same photo session.

Rick says that his real nightmare, thanks to SwissAir 111 (and the amazing writing in this Esquire piece), is this scenario. Warning: this is extremely difficult reading and will likely become a nightmare for you, too.

Then he told his wife, and she said, Until they phone us with the news, we have to believe. And the man said, But darling, they’re not going to phone with news like that. They’d come to the door —

And before he’d finished his sentence, the doorbell rang.

Two hundred thirty-nine people’s families are waiting for their doorbells to ring.