Archive of posts with tag 'editing'

Jul 2014: Rejecting Bad Writing Advice

There was a time when I was so starved for any writing advice, I’d take whatever crap would fall in. Granted, I was a Scientologist at the time, so you could say I was particularly primed for not only sources of bad advice, but also the unquestioned acceptance of same.

Over the years, I found that my brain became so constrained by all the bullshit I’d accepted that I found it impossible to write at all. I was bound by the red tape.

If You Want to Sell a Novel, Sell Short Stories First

Look, having any kind of respectable publishing credits helps. No question.

But not all novelists can write short. Even if they can write short, they may be nowhere near as good a short story writer as they are a novelist.

So here’s my revised answer to that: Write short stories because you want to. Submit them because you want to.

If they don’t speak to you, there are plenty of other, better ways to spend that time.

You’re Never Going to Make a Lot of Money as a Short Story Writer

I heard this last weekend. Verbatim.

Do I believe it’s true? No, I do not. Edward D. Hoch made a living as a short story writer.

Do I believe the odds are against you?

Sure, if you insist on thinking of it in terms of odds, which I don’t think is helpful.

Rather, I prefer to think of it this way: if you want to make a lot of money as a short story writer, you’d likely need to have a large number of relatively uncomplicated (in the sense that it’s a “short story” idea rather than a “novel” idea) ideas that you can write and polish to professional levels.

I know me: I have a smaller number of ideas but they’re more complex, and thus I’m a novella or novel kind of writer.

There’s also the issue that how much you make from short fiction depends on what venues are available for you to sell it, including film and television. Excluding self publishing at the moment, I’d argue that novella length has new life in the digital first markets.

Case in point:

We both have short stories and novellas, which frequently don’t make it into print except in collections or magazines. Those collections and magazines tend to pay token amounts if at all — contributor’s copies are common — whereas I’ve made over $8,000 from a novella published in 2011. Aleks and I co-wrote a short story that was released last year and has made each of us just under $2,000.

(Quoted from here.)

I’d say that most people would think $8,000 was “a lot of money.” Somewhat fewer would consider $4,000 ($2,000 x 2 writers) “a lot of money.”

But $10,000? For two pieces of short fiction? That’s a lot of money.

Ahh, but she writes male/male romance, you say.

I say that’s not the point. The point is that this construction, “You’re never going to make a lot of money as a short story writer,” assumes things one cannot possibly know about me and my future. It’s a prediction that my future will suck because someone else’s past (e.g., the speaker’s) has sucked.

Besides, Clive Barker did pretty well with this one novella. There are other examples, too.

Rather, it’s more helpful to know what kind of writer you are and whether or not that road would be easier or harder for you. If you’ve got a background writing short non-fiction, then writing short fiction may be easier for you.

Just because it’s a hard road isn’t a reason not to do it. A hard road is still a path, just a difficult one.

There are plenty of kinds of writing, if writing is what you want to do. If it’s not, there are plenty of things to do in almost any field. I really wish I’d understood this early on, because I felt roles were far more rigid when I was in high school. Maybe that was my mistake.

You Should Write in Third Person Because It’s Easier to Sell

To which I respond: my favorite novel’s in second person.

You’re four hours into your shift, decompressing from two weeks of working nights supervising clean-up after drunken fights on Lothian Road and domestics in Craiglockhart. Daylight work on the other side of the capital city comes as a big relief, bringing with it business of a different, and mostly less violent, sort. This morning you dealt with: two shoplifting call-outs, getting your team to chase up a bunch of littering offences, a couple of community liaison visits, and you’re due down the station in two hours to record your testimony for the plead-by-email hearing on a serial B&E case you’ve been working on. You’re also baby-sitting Bob—probationary constable Robert Lockhart—who is ever so slightly fresh out of police college and about as probationary as a very probationary thing indeed. So it’s not like you’re not busy or anything, but at least it’s low-stress stuff for the most part.

Second is very voicey, and it’s both a boon and a bane because of that.

Write in whatever viewpoint you feel happens to fit the story best, including second if you’re so inclined. If you’ve never tried it before, consider rewriting a scene in second person. See how it feels. Try the same scene in first and third emphasizing different viewpoint characters.

There’s no single right answer, but some genres are more frequently in one or the other.

I’ll give an example, though, of where I think first person really hurt the book.

Twilight.

Edward hovered over Bella at night in part because he was protecting her against rogue vampires that she didn’t know existed. Because the book was written in first person, it made Edward look more manipulative and controlling (and for worse reasons) than was actually true. because the book’s POV only showed things that Bella knew, and she didn’t know the whole story.

Read the partial of Midnight Sun (Twilight told from Edward’s POV) alongside Twilight. The two taken together, plus the movie, are a rare opportunity to learn from POV choices and mistakes.

So, if the motivations of another character are important to understanding the piece as sympathetically as possible, consider writing in third. Or, you know, some other POV that’s not a single first person POV.

That Odds Matter

I know a lot of heartbreaking stories in publishing. People having solicited manuscripts lost in piles in a publisher’s office for years. People having their novel abandoned when an editor goes on maternity leave and the replacement editor quits to go into the food business.

There are all kinds of narratives about publishing, and one of the ones I want to address is this: that there is such a thing as odds that determine whether or not you’ll sell a story or whether it’ll do well.

When I receive, say, 100 submissions for BayCon, the odds that I accept your story is not 1 in 100. I don’t roll any dice. Did you write the best story I received? Does your story mesh with my taste? Does it fit the theme better than other stories? (We don’t require that it fit the theme, but it doesn’t hurt.) That’s not a matter of odds.

More than half the time, I reject a story on the first page. I’m sure every writer did the best they could on their first page. Sometimes, it’s a matter of fit. I’ve said that the story we buy has to be family friendly, so “fuck” on the first (or any) page is a non-starter. And yes, I’ve rejected more than one story for exactly that reason.

It’s entirely random that I once, back in the Abyss & Apex days, received two short stories in a row with first sentences that had unintended flying trees. Yay misplaced modifiers. (Both of those were rejected on the first sentence.)

So you’ve survived the first page. Does your piece plunge immediately into backstory on page 2 or 3? That’s probably the single most common reason I reject stories on pages 2 or 3. And yes, this can be done right, and it so frequently isn’t. I’ve done it badly myself. Recently. (First draft, so there’s that.)

Let’s say I get to the end. More than half the time, I’ll still reject the story. Most frequently, it’s one of: the story you started isn’t the story you finished, or you didn’t nail the ending.

Another common failure is what I call the “this feels like a novel chapter” problem. I didn’t really understand this phrase until I saw it a few times as an editor. If you’ve raised more interesting questions/problems/plot points that are referred to in the narrative but don’t happen in the narrative present, it’ll feel like it’s a piece of a longer work. The only way I know of to fix one of these babies is to trim off the glittery parts that point out to other plot lines and story arcs until it feels like the story is resolved in the short form.

But selling a story? That’s not a matter of odds.

Let’s say the first page is solid and interesting, and pages 2 and 3 are strong enough to keep me going, and I finish the piece, and you have a great ending. You’ll likely wind up on the short list.

If anything in the process involves odds, then it’s what happens on the short list, because generally there are more pieces than there are slots we can publish. Since we’re picking newer writers, name isn’t a consideration. It’s just which stories the various people like the best. (I pick the short list, but that’s winnowed down by a small group.)

If I Had to Give Advice…

Three little things.

- Is this beginning actually the best entry point for your story for a reader? Not just where you started writing.

- Love your piece for what it is. Every piece has issues. Do what you can, then move on. I remember going over another author’s piece in a critique session. The author was worried about how it would be received because of a structure issue. I thought it was fabulous as it stood. It was later nominated for a major award, pretty much as I read it.

- Don’t overwork a piece in response to critiques. One of the death knells of an opening is often over-response to a critique like: “I wanted to know more about X in the beginning.” Then the writer edits it in, destroying the opening. Someone wants to know more about the character? Good. Read on.

Oct 2011: Miscellanea

First, I’ve been starting to send out rejection letters for BayCon’s flash fiction submissions. I’ve sent out about a quarter of them so far. Sorry for the delay, I wanted to re-read pieces because I wasn’t reading them in my best frame of mind with shooting shoulder pains for several weeks. I expect to get the reject/hold notices sent out this week; we’re starting to prepare the progress report the story will be in, so I need to get a move on.

Second, filtering words. It’s a difficult topic to search for, so here’s a good blog post on it. I don’t like all of her examples, but it explains why adding that layer of indirection isn’t always a great idea.

Third, showers. There I was in the shower this morning thinking it was one of the great wonders of civilization, and I realized I’d never heard (despite reading a lot of Libertarian books in my youth) how either Libertarians or the Tea Party would handle things like sanitation engineering and water management. What changed me from being Libertarian was seeing that public health simply wasn’t doable that way, and Laurie Garrett’s The Coming Plague was the final nail in the Libertarian coffin for me.

Sep 2011: Revision Habits

I’m really really really not a one-draft writer. At some point, I hope to dazzle you all with an illustration of how much I’m not a one-drafter, but today is not that day. Generally a first draft for me runs very short — somewhere between 1/3 and 3/4 of the final length.

To paraphrase how Tim Powers described my first drafts at Clarion: the stage is bare, the actors are auditioning as the scriptwriter’s in the front row re-writing the piece, and there’s only tape on the stage to tell them where to stand. They’re not quite that threadbare, but the layer I get written first is the plot (the piece he said this about, I’d gotten the bones down for a three-plotline short that was 3,800 words and, at most, 1/3 to 1/2 its final length).

Vylar Kaftan talks about her revision statistics, including her A, B, C system for stories.

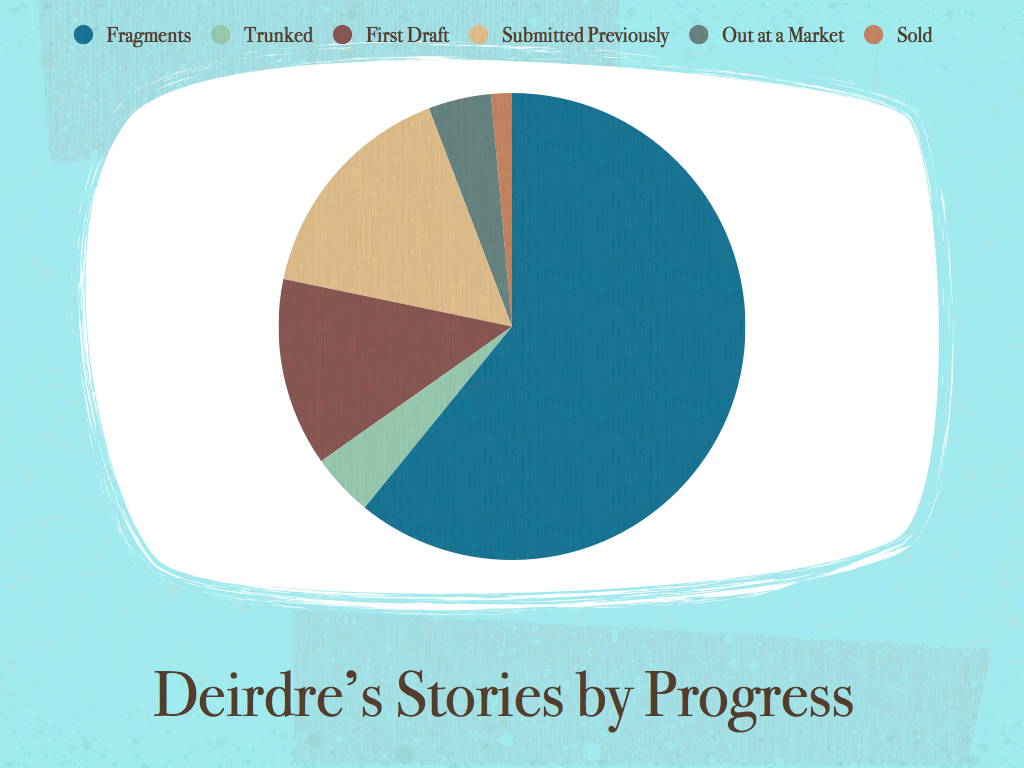

So below are mine. My first drafts fall kind of between A and B. Right now, they’re in C shape, but if I were done re-thinking them, they’d be moved up to the next categories. Submitted Previously, well, those are Bs. Out at a Market and Sold, obviously, are As.

Until such time as I have a sufficiently developed draft, there’s no point in categorizing it, but most of my pieces need significant steeping. The most recent piece I have out at market was one I wrote the first draft of in 2007. The oldest is one I wrote the first draft of in 1990, one of the first shorts I wrote and one of the most difficult pieces I’ve written.

Sep 2011: BayCon Submissions Breakdown

There’s often questions about markets’ submission breakdowns, particularly by sex. BayCon’s submission period just closed, so here’s the breakdown of the submissions we received over two months. All statements are rounded numbers; the charts are more exact.

1. We received twice as many Short Story submissions as Flash submissions.

Sep 2011: Publishing: Beating the Odds

Many of you know I’m the submissions editor for BayCon’s nascent fiction market (gentle reminder: submissions close 9/15; currently, submissions are running 40% flash and 60% short stories). In a practical sense, that means I’ll be reading all the submissions, culling it down to a short list for each of the Flash and Short Story pieces. Because I’ll be reading all of them, I added minimum and maximum qualifications so that we wouldn’t need a staff of editors to make the first cut.

I’ve heard from three different people that, because we’re only publishing two stories this year, they don’t think the “chances” of getting in are good, so it’s not worth tying up a story. Now, I’m not criticizing where people want to submit (your writing career, your goals, after all), but I can say something about the “chances” aspect.

Publishing Is Not a Lottery

Like acting, success in publishing is showing up at the right place at the right time with the right presentation on the right project. There are no “odds” except that the person seeing your work happens to give it the best read possible, and the number of times you submit a piece increases the likelihood it’ll find its way onto the right desk at the right time. Frankly, you don’t know what the “right” timing is because you don’t have the experience of the flow of submissions from the other side of the desk.

We’ve all heard stories about how many times J. K. Rowling was turned down, and I’ve seen the ream of rejections some friends have accumulated. Then there’s the flip side: some things sell first time out. “A Sword Called Rhonda” did. It also sold the second. That doesn’t mean I’m especially clever, truly it doesn’t. It just means I had the right piece at the right time for the right market. I’ve accumulated my fair share of rejections.

If there are 100 submissions, that 101st submission doesn’t affect the likelihood your story will get accepted unless your story was already borderline. If it’s superb, it’ll still be superb. If it needs work, it’ll still need work.

Anyhow, it’s not a lottery, and it’s not a game of chance. In this case, a good story could get you between $50 and $200.