James Blish: "Dianetics: A Door to the Future"

05 December 2014

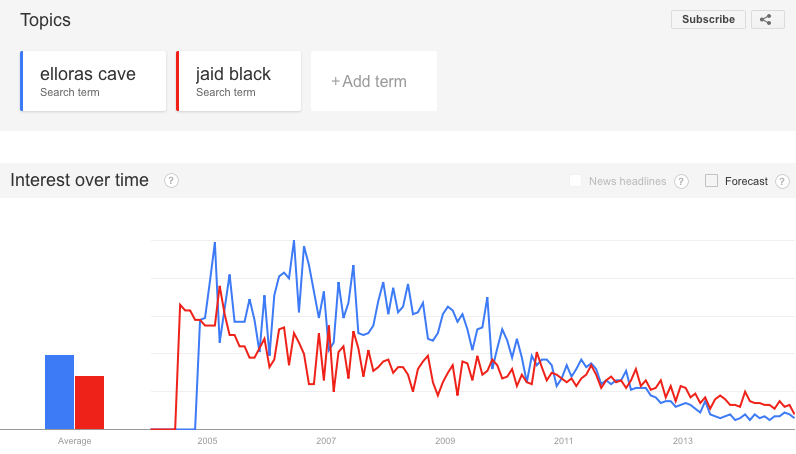

Long-time Scientology critic Rod Keller posted a link to an eBay auction that included a reading copy of a science fiction magazine (Planet Stories, November 1950) in which James Blish published a piece on Dianetics.

I’d already known that James Blish had been a Fortean, so I was expecting that Blish’s piece would be pro-Dianetics. However, the linked article led me to expect that Blish’s piece would be more intellectual than it actually is. > There are lots of reasons various people were drawn to the works of Charles Fort, as has been shown through these biographies, and some of them can be grouped into families: those who search for something simultaneously material and transcendent, beyond science; those who have trouble with authorities; those who wish to put forth an alternative science. One type not yet explored—but well represented among the Forteans—is the person who wants to be the smartest in the room. Tiffany Thayer himself fits into this mold in many ways. And so does James Blish.

Curious creature that I am, I ordered the mag, which arrived today.

Here’s the TOC, and here’s the article. (PNG 600 DPI greyscale scans, 14-16MB files)

Note: except for removing hyphenation and adding Wikipedia links, I’ve not edited the text in any way. If you notice any transcription errors, even a comma, please comment below or email me. I believe this is now in the public domain, but if you have a valid DMCA takedown request, use the email link at the bottom of every deirdre.net page.

Article Text

An increased life-span, freedom from 70% of all human illnesses and a major increase in intelligence—these are only a few of the benefits promised us by a new science called “dianetics.”

“Dianetics” is both the name of a recent book about how the human mind operates, and the general term used to cover specific methods of repairing, healing and perfecting the human mind.

Just how does the human mind work? Up to a few years ago nobody really knew.

Why does the human mind fail to work efficiently at times, or all the time? Another mystery.

If the claims made for the new science of dianetics are borne out, both those mysteries are now solved. Some of these claims are so flabbergasting as to stagger even the hardened science-fiction fan. For instance:

Dianetics claims to have cured many types of heart ailment, arthritis, the common cold, stomach ulcers, sinus trouble, asthma, and many other diseases, amounting to about 70% of the whole catalogue of human ills.

Dianetics also claims to have cured virtually every known form of mental disease. These cures have encompassed the severest form of insanity, workers in dianetics declare flatly.

Furthermore—and in this claim (among others) lies dianetics’ bid to be called a science—dianetics claims to be able to cure all these aberrations and diseases every time, without fail. At the time this is being written, some months before you will read it, dianetics has been tried on a minimum of 300 people, and, its originators say, has worked 100% without failure in all these cases.

Nor is this all, fantastic though what I’ve already written may seem to be. Use of Dianetic therapy on so-called “normal” people seems to produce changes in them which can only be described as dynamite.

“Normal” people treated by dianetic therapy, it’s said, undergo a rise in intelligence, efficiency, and well-being averaging a third above their previous capacity! In one case, a woman, the IQ—intelligence quotient—rose 50 points before the full course of therapy was run!

Such “clears,” as they are called, are said to be immune to any and all forms of mental disease, and to any and all forms of organic diseases caused by mental or emotional difficulties.

It might be a good idea to stop here and ask the names of the people who are making these incredible claims. They are none of them professional quacks, faith-healers, bread-pill rollers, or other forms of swindlers. They are all men with solid reputations, and all, as it happens, quite familiar to the science-fiction reader.

The leader of the new school of thought is L. Ron Hubbard, author of “Fear,” “Final Blackout,” and many other science fiction classics. By trade, Hubbard is an engineer.

Hubbard’s two principal confrères are John W. Campbell, Jr., and Dr. Joseph E. Winter. Mr. Campbell, of course, is widely known even to the general public as a government consultant in nuclear physics, the author of “The Atomic Story,” and to us as the editor of a top-notch science-fiction magazine. Dr. Winter, who by the way is an M.D., not a Ph.D., has published some science-fiction stories; but until dianetics came along, he was best known as an expert endocrinologist of unimpeachable reputation.

Hubbard’s book,* however, does not include any formal evidence for the claims. The Dianetics Institute in Elizabeth, N. J., is equally unwilling to offer authenticated case records or any other evidence of that specific kind. The book, dianetics men point out, offers the therapy procedures in complete detail. If you want case histories, perform your own experiments.

As it happens, one of the more spectacular cures claimed by dianetics took place in the New York area, and could be checked from outside sources. Jerome Bixby, editor of Planet Stories, checked it. The claim was so; hospital authorities who have no connection with dianetics as a movement vouch for it, cautiously but definitely.

My own personal tests of the therapy—on myself, my wife, and a friend (namely, Jerome Bixby)—haven’t proceeded very far as yet. But as far as they’ve gone, they check with the claims. The phenomena Hubbard describes in the book do appear. They appear in the order in which he says they appear. And they match his descriptions of them to the letter. Such after-effects as we’ve been able to observe also check.

If dianetics does work—and every check I’ve been able to run thus far indicates that it does—it may well be the most important discovery of this or any other century. It will bring the long-sought “rule of reason” to the problems of local and world politics, communication, law, and almost every other field of human endeavor—the goal of a 3000 year search.

*DIANETICS, by L. Ron Hubbard. Hermitage House, New York, 1950: $4.00. Hermitage, by the way, is the publisher of a number of books on psychology and psychoanalysis universally acknowledged to be serious contributions to the field.

(end of article)

The Cold Harsh Reality

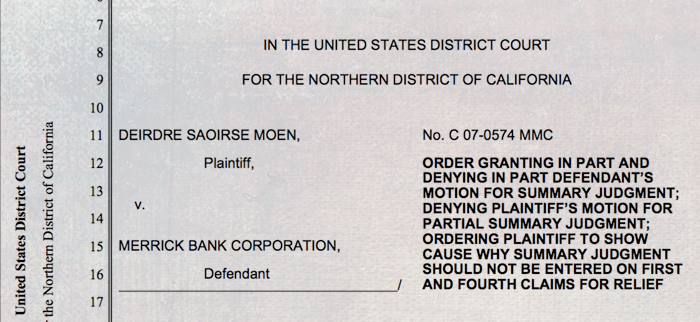

In 1946, four years before Blish’s article, Jack Parsons got a restraining order (and, along with it, a temporary injunction) against L. Ron Hubbard and his then-wife Sarah Northrup.

As we pointed out on Wednesday, Hubbard had met Sara in Pasadena at the home of John Whiteside “Jack” Parsons, the Caltech rocket scientist and occultist. The three of them had cooked up a business scheme that involved Hubbard and Sara going to Miami to buy a sailboat with money that was nearly all Jack’s, then sailing it back to California to sell for a profit. But once Hubbard and Sara went to Florida and bought a boat, they didn’t go anywhere, and Jack ended up suing them. The lawsuit was settled, Hubbard and Sara sold the sailboat, and then they went to Maryland, where they were married.

By 1951, the marriage had turned into a nightmare, and after they split, Hubbard did his best to erase from the record that Sara had ever been a part of his life.

So, ironically, had he but known Hubbard’s history, Blish wouldn’t have made a claim like “They are none of them professional quacks, faith-healers, bread-pill rollers, or other forms of swindlers.” Because, as it turns out, Hubbard was exactly that.

Also, in 1946, Hubbard was still legally married to his first wife, Polly.

In 1948, Hubbard was arrested and fined for petty theft.

In 1951, Dr. Joseph Augustus Winter left dianetics, publishing a book called A Doctor’s Report on Dianetics, critiquing that, among other things, Hubbard never wanted to have any minimum standard for testing subjects. Further, some techniques harmed some patients. Winter’s departure even made Time magazine.

About That Clear Thing

In 1979, I became Clear # 20,182. I later attested to Clear again (because, since the changeover in the late 70s, most people who’ve attested Clear in Scientology have had to do it more than once).

As I sit here writing this, I’m recovering from a cold. I have arthritis in one knee and the other hip. I had sinus trouble all through my Scientology years, but being on a CPAP at night does far more for that than Dianetics or Scientology ever could. I now have asthma, which I suspect is related to years and years of second-hand smoke, including working with smokers in Scientology.

Further, David Miscavige is widely rumored to have asthma. Anyone who’s known a lot of Clears has known some who’ve died of the various ailments Blish listed.

The claims of what Dianetics and Scientology cure are all bullshit.

James Randi’s Million-Dollar Challenge

The James Randi Educational Foundation will pay US$1,000,000 (One Million US Dollars) (“The Prize”) to any person who demonstrates any psychic, supernatural, or paranormal ability under satisfactory observation. Such demonstration must take place under the rules and limitations described in this document. An applicant can be from or in any part of the world. Gender, race, and educational background are not factors for acceptance. Applicants must be at least 18 years of age and legally able to enter into binding agreements.

Look, Scientology tends to leave its adherents cash strapped. I’ve seen it over and over again, and it’s a huge part of why I left. If the various claims in Dianetics and Scientology about paranormal abilities were indeed true (e.g., “exterior with full perception”), some one of those tens of thousands of Clears would have collected a million bucks from JREF.

And they haven’t.

Could be worse. You could be a desperately sad L. Ron Hubbard in your last days asking one of your assistants to build you an assisted suicide machine so you could die.

But this Blish article? A puff piece where he says he’s audited his friend, who, oh yeah, also happens to be the editor of the magazine said puff piece is printed in? And said friend checked one of the more “spectacular cures” (which, you note is never specifically identified)?

That’s horseshit.

Blish should have been ashamed of himself.

At best, the techniques used in Dianetics and Scientology are talk therapy.

Most of the time, they’re not even that good.